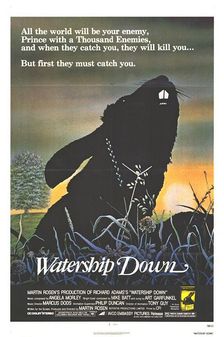

When I was very young – about the age of nine or ten, actually – I saw the film version of Richard Adams's Watership Down. I was entranced by the often disturbing visuals (my parents had no idea what the film was like, as they never bothered watching it with me, thinking it was "just a cartoon") and captivated by the story. The idea that rabbits had such traumatic lives (and deaths) was something so absolutely foreign to me, I simply couldn't grasp it. I loved the film so much, I was inspired to try to write my own story with similar themes – the problem was, I could barely understand what the film was really about, and so my pale imitation remained just that: an imitation.

After I'd watched it countless times (I literally lost track of the viewings), I finally noticed that the film was in fact based on a book. The emotion which followed this discovery was indescribable, as though I'd just had a moment of divine intervention in my life, because I loved books. I carried my favorite titles around everywhere I went, reading them every chance I got, even though I'd long since memorized them.

Finally, I found myself in a bookstore, perusing the titles away from the children's fiction section, and after standing on my tip-toes and craning my neck, I spotted it, way up high on a the top shelf. The spine was an autumnal mix of yellows and golds, the title framed in a box of brown so dark it was almost black. I know I must have gasped, or made some sort of sound of surprise, because a man browsing in the same aisle was startled to hear it. I stretched out my arm, cursing the fact I was so short, unable to reach the top shelf even though I hopped up and down to the best of my ability. The man gave me a funny look, then, understanding my dilemma, smiled at me.

"Do you want one of these?"

Oh-my-goodness-yes-yes-YES!!!

"Yes, please."

"Which one?"

"Watership Down." I was so excited I could hardly stand it. He kindly pulled the book off the shelf and handed it to me, and after I managed to squeak out a "Thank you!" I went barreling down the length of the store looking for my mom, clutching my treasure close.

I found her at the front of the store, looking through the bargain books.

"Did you find anything?" she asked, then turned her head and looked at me while I danced in place like a hyperactive bundle of pure energy on a sugar high, needing to pee. Desperately.

"Iwantthisoneplease!"

Mom frowned. "Oh, Kim. No."

WhaaaaAAAA???

"Why not?"

"That's a book for grownups."

"So?"

"You'll never read it."

"Sure I will!"

One hand on hip, she turned to fully face me. "How many pages is it?"

I opened the book, still jogging in place. "Four hundred seventy-eight pages."

Mom sighed. "It's too big. There's no way you'll read that whole thing."

"I-will-I-will-I-will! I promise! And I won't ask for another book until I'm done with it!"

Mom sighed again. "Fine. But you can't get any more books until you're done with that one. And I want to see you reading it."

She knew this was the biggest threat she could level at me. I got a book at least every other week. I looked forward to those books as much as I did Christmas or my birthday. "Okay. You will."

And so I went home with my very own copy of Watership Down in my hot little hands, resisting the urge to open it until I could get home and savor the first pages. On the ride home, I stared at the cover, committing it to memory, loving those earthy colors, the rabbit on the front, the golden grass in watercolors on the back cover, the red outer edges of the pages.

Once I was home, I bolted to my room and sat on my bed, then turned on my bedside lamp. I perused the maps on the first few pages, stumbled over the segment of Agamemnon quoted before the chapter's start, and then dug in and started reading:

The primroses were over. Toward the edge of the wood, where the ground became open and sloped down to an old fence and a brambly ditch beyond, only a few fading patches of pale yellow still showed among the dog's mercury and oak-tree roots. On the other side of the fence, the upper part of the field was full of rabbit holes. In places the grass was gone altogether and everywhere there were clusters of dry droppings, through which nothing but the ragwort would grow. A hundred yards away, at the bottom of the slope, ran the brook, no more than three feet wide, half choked with kingcups, watercress and blue brooklime. The cart track crossed by a brick culvert and climbed the opposite slope to a five-barred gate in the thorn hedge. The gate led into the lane.

Time passed. My confidence was a tad battered, but I emerged from my room after completing the first few chapters, feeling strange. It wasn't at all what I had expected, but not in a bad way. It was like the movie, but different. It was also very different from what I'd written for myself, in so many ways. It was richer, layered, full of details which – when I understood the words, and there were a few I honestly couldn't fathom at the time – pulled me in and made me feel like I was really, truly there in that doomed warren of rabbits, needing to escape but not sure how to do so.

"So? How is it?" Mom asked, and I know now she expected me to say "It's too hard!" or "I don't understand it!" or something along those lines.

"It's very… descriptive. There's lots of description in it."

"Oh, really?"

"Uh-huh." I nodded and then looked down at the book, still in my hand. I looked up at her again, wishing she could understand what I felt at that moment. The wonder, the rightness, were beyond my ability to explain. So I settled for "Thanks, Mom," and went back to reading in my room.

I read the book more than twenty times that summer. I re-read it every year, and even now, thirty years on, I discover something new and beautiful with every reading. To this day, it's the detail in the descriptions I savor. I read those details, and the way they unfold, painting the scene, makes it seem as though I've closed my eyes and opened them in another time and place.

Yes, I can appreciate the allegory, now. I can see the symbolism and understand the themes threaded through the narrative, almost all of which flew over the head of my nine-year-old self. I no longer try to write in the same style, but in the back of my mind, as I describe a place and try to set the stage, a desire to draw the reader in as Adams drew me in, so utterly and completely it was a shock to stop reading and find I wasn't actually there, remains.

One day, I might just manage it. But until then, the primroses are over, and there's a gate leading onto a lane I need to stroll down. It's been a while since my last visit.

(This article originally appeared on the Power of Language blog in 2010.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed